If the NFL is serious about caring for potentially concussed players, why doesn’t it remove ultimate return-to-play decision-making from the team’s doctor, and so empower the unaffiliated neurotrauma consultant assigned to every sideline?

Critics of the NFL’s sincerity in concussion management often ask this. And indeed, it would seem to make the most sense, as this “UNC” is not employed by the team, as the team doctor is, thus any perceived conflict of interest would be removed.

The NFL’s chief medical officer, Dr. Allen Sills, answered this question — and others pertaining to the league’s ever-evolving protocols on concussion care — in a phone interview on Wednesday.

Wouldn’t such a transfer of in-game return-to-play authority better aid the player? In reality, no, Sills said. Besides, UNCs “in practicality” already possess that authority. Or co-authority.

“What I mean by that is it is a joint, consensus decision that’s made together between the team physician staff and the independent staff,” Sills said.

“I liken it to what happens in the hospital when we have a patient in the intensive care unit. As we go on rounds, as a group of doctors we discuss our ideas, our hypotheses, and we reach a group consensus about what’s the best course of action for each patient. And I think that’s what’s done in the concussion protocol. You’ve got the input of the spotters (the “eye-in-the-sky” booth athletic trainers), the team physicians and the independent personnel. That unaffiliated doctor and the team doctor arrive together at a decision.”

Sills then dropped this news, regarding the rarity of disagreement.

“I can tell you that in the four years that I worked on the sideline as a UNC, and now the year that I’ve been with the league, I’m only aware — of all those evaluations, which obviously is in the hundreds — of one situation where the unaffiliated UNC and the NFL team physician came to different conclusions after reviewing all of the evidence,” he said.

“And I’m proud to report that, in that case, the team physician did in fact go with the recommendation of the UNC because it was the more conservative recommendation — to keep the player out of the game. So I understand that (conflict of interest) concern, but in reality these medical professionals always land at the same place in virtually every case. The one time they didn’t — and I would speculate in future cases, too — they’re going to go with the more conservative recommendation. They’re going to land on the space of keeping the player out of the game, because they want to be as conservative as possible.”

So, then, why not leave the decision entirely to the unaffiliated professionals?

“That is not a scientifically sound idea,” Sills said, “because there is a lot to be said about someone who knows the player’s baseline. For example, with some concussions the only sign they may have is a personality change. We’ve seen that time and time again. I’ve seen that in my own practice.

“So if you never met that player before game day, sure, you can see if he has a seizure on the field — but it’s that subtle change in personality they would never pick up on. So I think the best isn’t ‘either/or’ – it’s ‘and/both.’ ”

Until filling the league’s newly created position of chief medical officer last March, Sills was professor of neurological surgery, orthopaedic surgery and rehabilitation at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, where he founded and co-directed the Vanderbilt Sports Concussion Center.

Last year Sills co-authored the fifth incarnation of the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT 5), and saw to it that the NFL, for the first time, implemented that document’s sideline and locker room best practices suggestions.

The league further upgraded the sideline-diagnosis protocol in December, to add seizure-like symptoms as an automatic no-return symptom for head-hit players, and — in a pilot program — to add a “central UNC” watching on TV to the list of medical professionals empowered to stop play so a player can be evaluated.

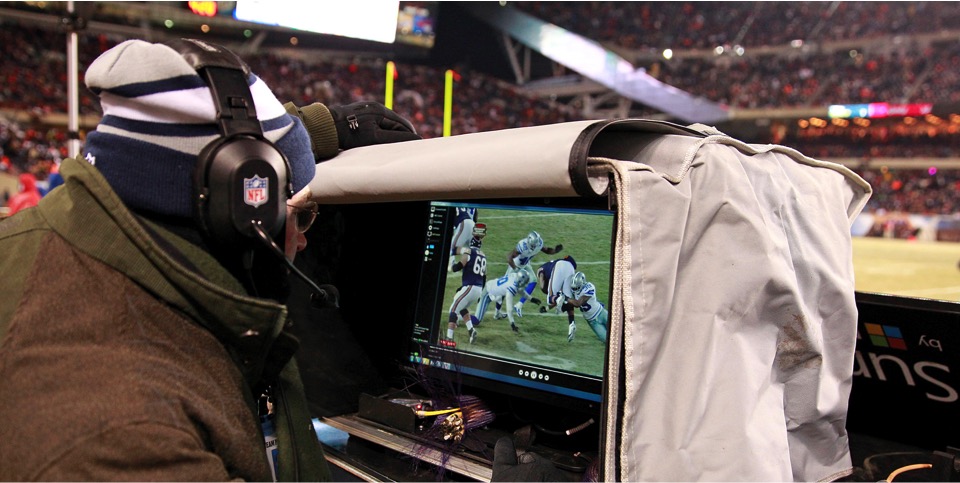

“You might ask, ‘How is it that everybody sitting at home can have a better view of that than the doc on the sideline?’ ” Sills said, in explaining the pilot “central UNC” program, which will continue through Super Bowl LII. “As somebody who has been on a sideline for over 20 years as a doctor, you don’t always see the field from the sideline. It’s a chaotic place, there are some very large men who play this game and trying to see all parts of the field in real time is difficult.

“We felt an improvement would be to provide a central UNC who would be overseeing those broadcast videos.”

Reports in December said Sills himself would act as the central UNC, watching the same broadcast feed as the viewer at home either at league headquarters or, in some cases, elsewhere. Untrue, Sills said in Wednesday’s interview.

“In fact, we used some of our regular UNCs for that role … someone who doesn’t work for the clubs, but rather is functioning just like our (on-site) UNCs on game day.”

A suggestion: the central UNC should watch action only via “real-time” fibre-optic technology at the NFL’s central replay command centre, so as to avoid the typical cable or satellite feed delays of up to 15 seconds which, if the intention is to pull a head-hit player before the next play, could prove logistically undoable — that is, too late — especially when a team goes hurry-up.

NO MORE TACKLE IN ILL.?

A coalition of Illinois politicians and concussion-prevention advocates on Thursday launched a campaign to ban youth tackle football in that state.

State Rep. Carol Sente joined a coalition of ex-football players, medical experts and advocates at a news conference in Chicago to urge passing of a new legislative proposal called Dave Duerson Act to Prevent CTE.

The proposed act is named in honour of the former Notre Dame and Chicago Bears star who killed himself at age 50, and was posthumously found to have CTE, a disease found in the brains of dozens of deceased former football players.

Illinois would be the first state in the U.S. to ban youth tackle football, according to Chris Nowinski, CEO of the Concussion Legacy Foundation and one of the initiative’s chief advocates.

By John Kryck for the Toronto Star

January 25, 2018

Source